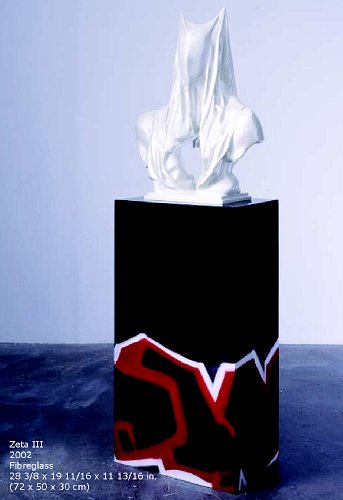

Steven Gontarski

Praha

interview with Tim Marlow, February 2004

Tim Marlow: The sculptural fragment is often the means through which we experience the classical world. It also has connotations of violence. Do these notions underpin your thinking in any way?

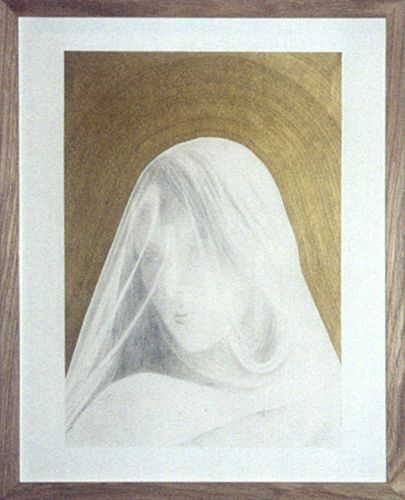

Steven Gontarski: I'm used to seeing the sculptural fragment in museums or books and since it usually appears in such authoritative packaging, such as a museum display or a perfectly composed picture in a textbook, I find it easy to forget about the fragment`s overall history and its relation to a larger sculpture (it's framentation) and accept it as an independent, whole object, more like a sacred relic. Of course relics, we're meant to believe, are actual parts of various saints - such as an organ or so of an actual human - but when an object itself becomes placed in a reliquary and is given the sacred treatment it carries so much power unto itself, it becomes its own being. Maybe this is related to fetishism? I do see the sculptural fragment as a means through which we experience the classical world, perhaps like a keyhole or lense, giving us access into an entirely different space.

Tim Marlow: The new work is clearly linked to your full length figure Prophet sculptures. Do you see them as part of an ongoing series?

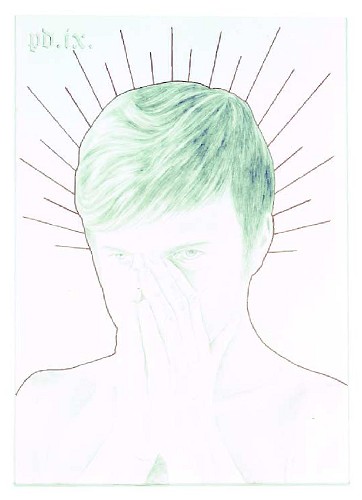

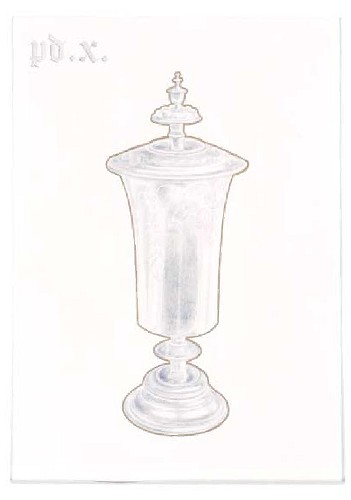

Steven Gontarski: I see practically everything as part of an ongoing series. I make the Prophets and busts and drawings to fill in different angles of a myth I'm cobbling together. When I say myth, I don't necessarily mean a literal story with characters that relate to one another and follow a narrative - it's more of a space defined by memories, belief and faith. I borrow many details from already-existing myths and stories, whether religious, secular or contemporary, like the 'urban myth', because these details are charged.

Tim Marlow: This is interesting. You speak eloquently about fictions but of course sculpture is a physical fact. However, because of the way you use materials, where the surface is highly refiective, or now with your use of glass, it's transparent, there is a sense of dematerialisation. Do you recognise this kind of slippage between fact and fiction?

Steven Gontarski: When presenting information to other people, sometimes there's little difference between fact and flction. The manner of storytelling reveals meaning. Two people faced with the same facts can assemble them in ways to suggest entirely different things. At the same time, messages that have been completely fabricated can resonate with our personal experiences and feel absolutely true. Often small memories flash in my head and I'm not sure whether they actually happened, if I dreamt or read about them. To my mind's eye a dreamed event may have equal value to an actual event because I experienced both of them in some way and tucked them into memory. I like highly reflective surfaces and the motif of veils since they don't allow penetrability - they keep our eyes on the surface and allow 'what's inside' to remain unknown, its core or 'actuality' is in doubt and all we have to work with is what it appears to be. I flnd glass and plexiglass to have similar effects in that they're insubstantial. They suggest rather than substantiate form. Also, and most importantly, I simply like the look of these materials.

Tim Marlow: The gesture of the hands is one of Benediction - at least that's one way of reading it. Does the spiritual dimension play a central role in what you're working towards in your art?

Steven Gontarski: Of course. These things I mentioned before; belief, memories, faith, emotion - are the components of spirituality. They co-exist in some kind of floating, changing space. Symbols are the cues that link people together who share some of these beliefs and memories. It's not necessarily a religious phenomenon, I often feel spiritually connected to people who listen to the same music as me and love it for similar reasons. It makes me nervous but also fascinated when spirituality meets structure… let's call it religion. I like to use religious imagery because it's often beautiful, like the pentecostal tongues of flre for instance - how amazing - or the Benediction, because they're linked to myths which carry a degree of gravitas.

When I use religious symbolism I don't mean to perpetuate any biblical myths, I want to make my own (not necessarily Christian) versions and in doing so, show how adaptable religion is to suit social needs of a particular time and space. Here's an example - lately some press attention has gone to the teen virgins of the US. Apparently vows of abstinence led by Christian youth group leaders are becoming more and more popular. Lots of these kids actually make symbolic gestures such as wearing rings as though they're married, to prove their commitment. It's supposed to cut down on sexually transmitted diseases among young people by pathologising sex and fetishising marriage and all its sanctity (my interpretation of course, not theirs). Meanwhile federal money supports these campaigns that claim that safe sex doesn't work. It's amazing to me how religion can be adapted to dovetail perfectly with an ultra conservative government so that people can actually do things like wed their own chastity in quasi-religious ceremonies. The virgins seem totally convinced of their actions since their decisions were 'religiously' rather than 'governmentally' led; they even have the symbolic proof.

I certainly don't want to undermine the reverance and the deep rooted spirituality with which many people approach religion. In fact I try to treat spirituality with as much beauty, stillness and truth as I possibly can. I'm trying to offer a blessing of my own.

Tim Marlow: Why the flame?

Steven Gontarski: Because it's miraculous, violent, and erotic.

Tim Marlow: Does the idea of sculpture as monument appeal to you?

Steven Gontarski: I'm not particularly interested in the monumental or in grandeur for it's own sake but I'm drawn to the monument as a sculptural form because it's meant to help us remember things/people and prompt reflection. Its association with death gives it dual reverbations; one of grim reality and one of spiritual timelessness or perhaps even a transition into a different space.

Tim Marlow: People often flnd your work sexual in its references or just sexy in its impact. Is making sculpture in any way an erotic activity?

Steven Gontarski: I wish that making armatures and sanding down plaster were erotic activities. I try to make things that I want to see, materialise the way I think the world should be, not as it necessarily is, so forms become idealised. I don't consciously think of the sexual element when I work but I can't deny that eroticism holds a high place in the process of idealisation.