Alva Hajn

Bratislava

Exhibition: September 21 - November 30, 2018

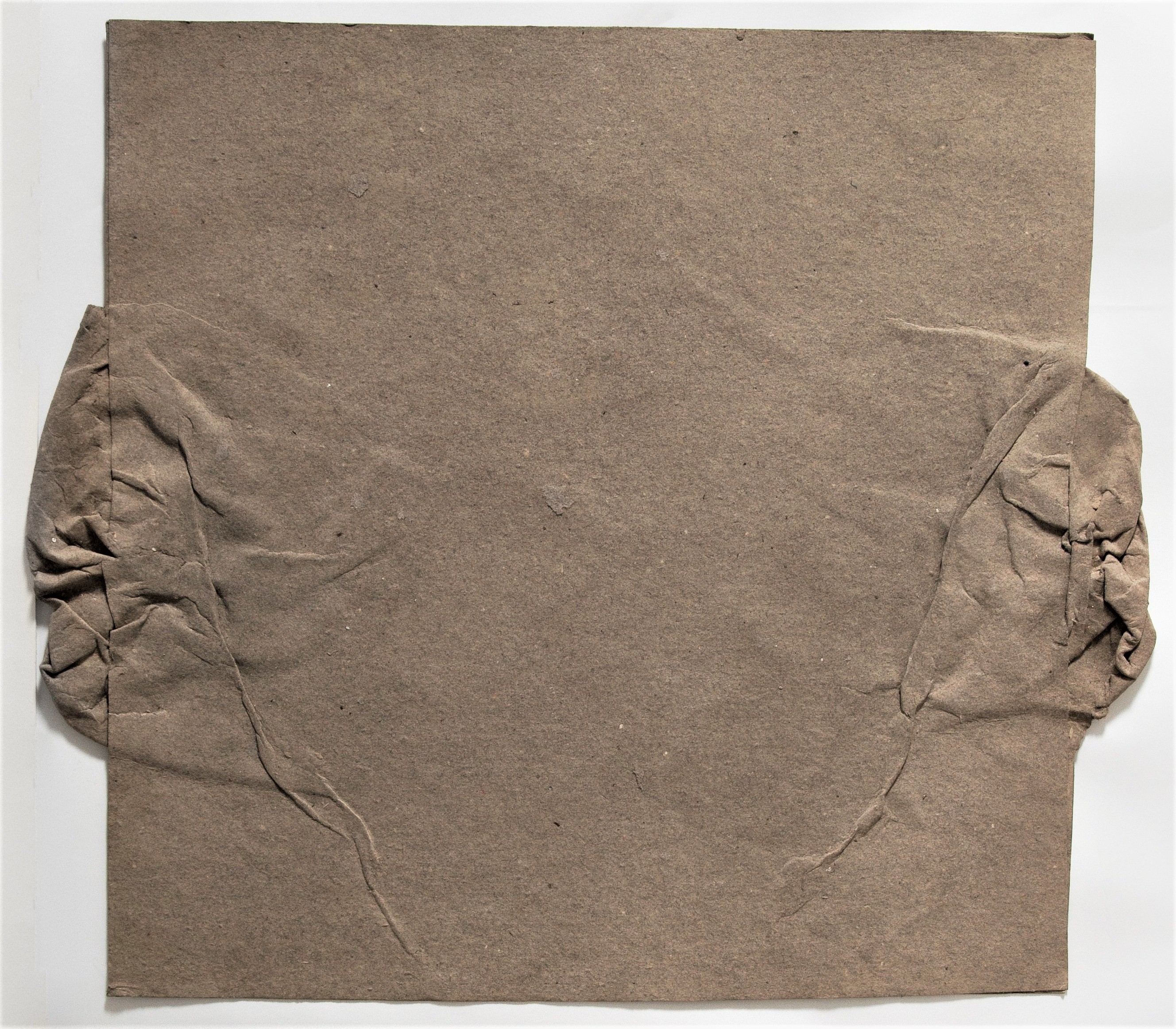

Gandy gallery is pleased to present the first solo show of the Czech artist ALVA HAJN. This exhibition presents mostly his works from 1970s and 1980s, such as paper reliefs and small sculptures.

I cannot answer an opening question. The question is: what impressed Nadine Gandy on Alva Hajn, why she decided to present his works today? We have to ask her and she will certainly be able to answer it.

Besides the works themselves, what kind of questions does this exhibition raise, how can we understand this little-known work in 2018 when it is shown in a space integrated in the contemporary theoretical and artistic world?

My relationship to the work of Alva Hajn is based on a series of coincidences that I briefly mention here. During my art history studies I worked as an assistant on projects organized by Institute of Art History of the Academy of Sciences. One of the tasks, which I was supposed to accomplish, was to prepare several keywords for a long-term project called “New Encyclopedia of Fine Arts”. It was a broadly conceived scientific encyclopedia of figures, collectives, groups and movements of the Czech art. At the end of the preparations of the encyclopedia, there were several authors left that the editorial board wanted to include to the publication, but there was no art historian who would prepare their keyword. Alva Hajn was among them. So this is how I met him:

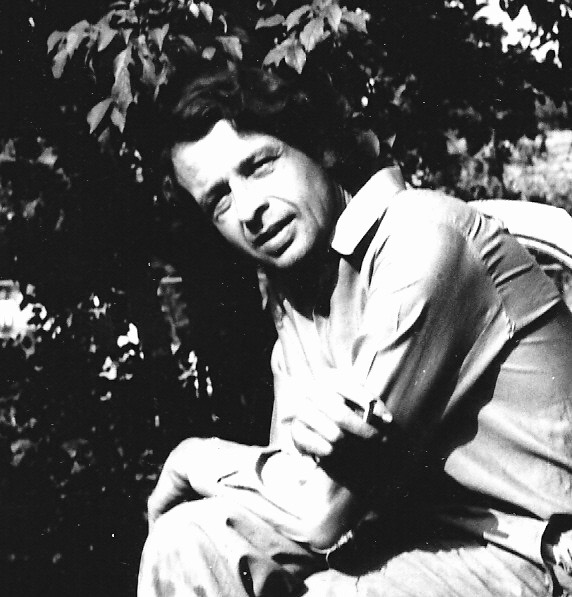

Alva Hajn was born in Polní Chrčice (Pardubice), 1938 – Polní Chrčice (Pardubice), 1991. Secondary education at the Art School in Prague (1953 – 1957). During these years he was influenced by the study of the works of Karel Černý and Jindřich Průcha. He spent the sixties and the seventies in the cultural enclave of the Pardubice artistic collective (F. Kyncl, J. Procházka, J. Lacina), in the mid-eighties he moved back to the village Polní Chrčice, to his native farmhouse which he turned into a studio. In the early sixties, he was influenced by the cubist-expressionist paintings of Kubišta, especially in the dark drawings (Mom, Illustration for the “Process” by F. Kafka), where the cubist shaping and understanding of the role of light dominate. He transforms these qualities to something rustic, capturing his existentialist condition of anxiety. He creates only things and portraits of the closest friends, family and land from Chrčice. In the seventies he managed to get sculptural commissions for interiors, as well as exteriors. They were both figural and abstract in nature, characteristic rather by the imbalance and inconsistency specific for a large production, with the flavor of a formal experiment. His drawings and paintings are formally freer and thematically more focused. In the seventies, the titles of his paintings are related to the figural and abstract depictions of the corporeality and relations between a man and a woman, a religious topic also appears, in connection with a piece of Chrčice chapel or the compositional contrast of a horizontality and a verticality. At the turn of the seventies and eighties he passes to abstract painting structures, often using only a white and black colour. The themes include spiritual states and emotions in relation to material, variations and a search for an intuitive language of a material abstraction. In the eighties he paints and composes arrangements from lines, geometrical shapes and fragments of found materials (wires, concrete, plaster).

That was the slightly modified vocabulary keyword from the first half of the nineties. It brings to us several insights characteristic for a view of his work. Hajn was one of the authors who, within a wider isolation of the world behind the “iron curtain”, were isolated for the second time – by a choice or simply by a social ability to work outside the main cultural center (Prague). To a certain extent, this choice was determined by the conditions from which he came and to which he avowed. In his catalogue text P. Ondračka speaks about two groups, which took shape during Hajn’s studies at the Art school in the fifties. The first one included students who, speaking in simple terms, understood the artistic practice as a matter of metropolitan identification, as a cultural production of originality. While the “rural” group to which Hajn belonged, perceived art as an authentic production related to the nature and its processes of the constant transformation, to a certain extent, as a craft. In his life Hajn did not exhibit very much (what was more the consequence of conditions of the double isolation, than his own will), avowing to an artistic work which arises in an isolated concentration, while drawing impulses from its own continuity and discontinuity. Thus, he was relating to the heritage of artistic solitaries who have a strong tradition in the Czech context, such as Josef Váchal, Bohuslav Reynek working on a farm in Petrkov and whose works Hajn collected, or Václav Boštík, Adriena Šimotová who, despite living in the center, developed their works on the premises of an authentic search. Hajn did not comment his oeuvre, however, after his death, it received art historical commentaries, thanks to an exhibition in the gallery Klatovy Klenová in 1997.

It was surprising for me to find out that during his studies Hajn was strongly inspired by an example of the Czech expressive realist Jindřich Prucha (1886 – 1914) about which I learned just recently[1]. Prucha, who came from modest conditions of the Czech countryside, painted landscapes “freezing in the shed” what made him an ideal example of the authentic approach to work for “villagers”. When I started to work in the National Gallery in Prague in the second half of the nineties and made an inventory of the whole painting collection, I came across Prucha’s paintings by which I was fascinated, what later led to an exhibition organized by the National Gallery. Even in the short period of time (he died at the age of 28) Prucha performed quite courageous synthesis of the German and French expressionism (group Osma) with the experience of his rural background and environment. Not only did he thematize his native land of Czecho-Moravian highlands, but also he dramatized and psychologized it in a way that has no parallel in the history of the Czech painting.

Another de facto accidental moment of returning to Hajn’s work was collaboration with Guillaume Desange on the exhibition “Ma’aminim” which dealt with political and social movements in France in the 1960s and 1970s. For the Prague edition of the exhibition the curator needed to add “dark abstract” works of the artistic nature, so we suggested him the structural graphics of Vladimír Boudník and the works of Alva Hajn. In the context of socially and politically engaged exhibition, Hajn’s paintings worked great as metaphors for the topic of a struggle. Struggling between the generic language of the abstraction and psychological contents, which the author wants to share through.

The question which is posed in front of us by the current Hajn’s exhibition, is what these completely vernacular connections from which Hajn’s work grows, can communicate nowadays and how to perceive it in the broader context of the global art history of the sixties to the eighties? It seems that what makes them attractive and sharing, is just what made them local and isolated before. Their starting point is a reflexion of the first Modern art (expressionism, cubism, abstraction) but fifty years later – in a situation of the relative post-war isolation of the Eastern Europe, as well as in the second isolation within this environment. Hajn’s model of work did not attempt to respond to current events elsewhere, it inclines to a model of a solitaire concentrated creation which develops these starting principles without the need to compare with others. Hajn was not afraid to experiment and try, he was not pushed by any external reason. This results not only in the imbalance, but also in the fact that some of his works remain original in the international comparison.

The development of the modernist patterns led him to solutions, which should not be compared to the Art informel but asynchronously to the original pre-war basis. Material objects from the eighties could, in the context of the East European avant-gardes of the 1960s (Karel Malich, Stanislav Kolíbal, Mária Bartuszová, etc.), seem as their vernacular imitations. However, they are distinguished by a different aesthetic pathos in their execution and by a different reasoning. The East European avant-gardes (especially in the Czech environment) carried on a constant aesthetic dialogue with the Western art, what was not the Hajn’s case. From the beginning Hajn appropriated, without much reflection, the modernist vocabulary which, subsequently, he used completely freely, without any external pressure, for his own concentrated play and search in which the conditions of the author living in the isolation from the urban culture, employing what is available, in the symbiosis with the craft and agricultural production, reflected aesthetically. I do not think that it would be adequate to create around Hajn a myth about the agrarian modernism, rather it is a comprehension of the aesthetic mode of production in relation to a material and to a finality of the artistic artefact. While the relation of the avant-garde to a material was determined by the cultural tradition and the artefact was destined for a gallery or a museum, Hajn’s relation to the material had a more prosaic, rural background and his works, rather than for a museum presentation, aimed to show a pragmatic realization of an idea, how the artistic practice outside “ideal” conditions of the cultural center looked like. Nevertheless, these observations should be put in relation to the post-war avant-gardes. Their goal was the liberation of the artistic production from the bourgeois aesthetics, un-schooling of the art, a realization of a postulate that anybody is an artist. Therefore, we do not have to look at the specifics of Hajn’s oeuvre through the romantic optics of the rural modernism, but as a phenomenon of the modernist realization of some of the avant-garde postulates in the East European historic conditions.

Text by Vít Havránek

Vít Havránek is a theoretician and organizer based in Prague, Czech Republic. Since 2002 he is working as a project leader of the initiative for contemporary art tranzit. He worked as curator for the Municipal Gallery, Prague and the National Gallery in Prague. He lectures in contemporary art at the Academy of Applied Arts, Prague.

[1] See Pavel Ondračka, Alva Hajn: Dílo jakožto rovnice, in: Alva Hajn, Marcel Fišer, ed., Galerie Klatovy Klenová, 1997, p. 14.